Saxon Weapons

Around AD400, the Saxons came

to England with a reputation for warlike ferocity

and a strong reverence for the sword as a potent

symbol of both strength and martial spirit. The mass

of Anglo-Saxon warriors normally carried a shield

and dagger (seax) and fought with spears and axes.

More sophisticated members of the nobility and

professional soldiers carried spears (similar to the

Roman pilum) and swords.

The Saxon Sword

Through excavating

numerous graves in England, archaeologists have

learnt that the Anglo-Saxons often chose to bury

their dead with a full array of weapons and armour.

These grave weapons are normally of great beauty and

artistry, highlighting the belief that a warrior

needed to take with him into the afterlife (or in

later Christianized Anglo-Saxon society

—

heaven), material

proof of the great status afforded to its owner

while alive.

Ownership of both

sword and spear defined the Anglo-Saxon warrior as a

free man, compared with slaves (oeows) who were

forbidden from carrying any arms. The great cost of

acquiring a serviceable sword would also have shown

the owner to be a man of means and rank. A typical

Anglo-Saxon sword had a long, straight, double-edged

blade with an average length of around 90cm

(35.4in).

The Saxon Spear

In Anglo-Saxon

burial grounds, the spear is by far the most common

type of weapon unearthed and is regarded as the

primary armament of the Anglo-Saxon warrior. All

ranks of society carried the spear, from king and

eon (earl), to the lowly ceonl (free man of the

lowest rank) or conscripted peasant. Comprising a

leaf- shaped iron spearhead and wooden shaft,

traditionally made of ash, a typical spear measured

around 1.5—2.5m (4.9—8.2ft) in length.

ABOVE:

In

a detail from the Bayeux Tapestry,

1082,

the English soldiers, who are all on foot, protect

themselves with a shield wall while the Normans

mount a cavalry attack.

The spear would have

been held in one hand while a shield was grasped in

the other. It was extremely effective when used in a

mass formation, most notably the famous Anglo-Saxon

“shieldwall” or shildburh. It was this shildburh

that faced William the Conqueror at the Battle of

Hastings. It was only compromised when the Normans

feigned a cavalry retreat, deliberately allowing

themselves to be chased, whereupon they suddenly

wheeled back and charged the openly exposed

Anglo-Saxons. This was a fatal error by the pursuers

and dictated the eventual outcome of the battle.

In contemporary

descriptions of the Battle of Maldon in AD991

(situated on the modern-day Essex coast in England),

the Anglo-Saxon Eon Byrhtnoth is depicted as

throwing two types of spear or javelin, both long

and short. It is interesting that it was only when

injured by a Viking spear, and finally exhausting

his supplies of spears, that he eventually resorts

to using his sword.

ABOVE:

A

winged Saxon spearhead (top) with double wings to

prevent an opponent’s blade traveling down the

spear. A slim spearhead (bottom) to allow

penetration through armor.

The Saxon

Battle-axe

Anglo-Saxon

warriors inherited the two-handed “bearded”

battle-axe from earlier generations of Danish Viking

invaders who had employed it with great effect to

board enemy ships. The Anglo-Saxons soon became

extremely proficient at using the battle- axe. With

its 1 .2m (3.9ft) haft and large honed axehead of

around 30cm (11 .8in), it had the capacity to

shatter shields and inflict grievous wounds. Swung

from side to side, it could cut down a mounted

soldier and his horse in a single blow.

These long axes

were wielded by the huscarls (King Harold’s personal

bodyguards) and described as cleaving “both man and

horse in two”. One of the drawbacks of using the

two-handed axe is that while raised above the head

it momentarily left the user dangerously exposed at

the front to sword or lance thrusts. Despite this,

the sight of a mass of axe- wielding Anglo-Saxon

warriors approaching the enemy’s ranks normally had

the desired psychological effect, with many

contemporary accounts noting that the opposition

simply fled from the battlefield.

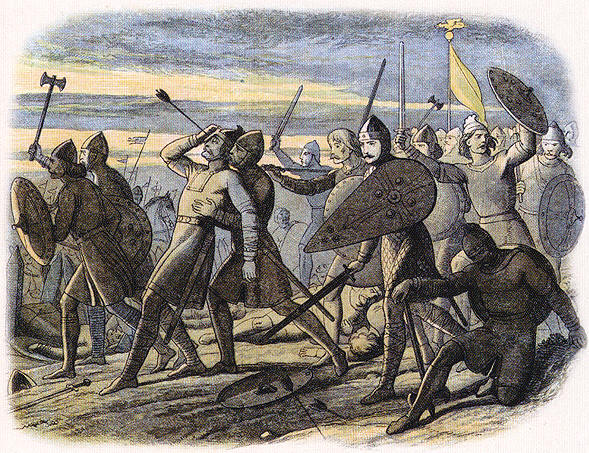

ABOVE:

A

later depiction of the felling of King Harold II (c.1022—1066)

by a Norman arrow at the Battle of Hastings (1066).

Anglo-Saxon Women

Warriors

It was not only men

who fought and became respected heroes during the

Anglo-Saxon period. Recent archaeological

discoveries have raised the possibility that women

also took part in warfare.

In the village of

Heslerton, in North Yorkshire, England, two female

burials were unearthed in 2000. Dated to around

AD450—650, both women had been buried with spears

and knives. Just outside Lincoln, a town in eastern

England, the skeleton of another Anglo-Saxon woman

warrior

(c.

AD500) was found

with a dagger and shield.

Procopius

(c.AD500—565),

the late Roman Byzantine scholar, notes in his

history of the Gothic Wars (AD535—552) that an

unnamed Anglo-Saxon princess, from the tribe of

Angilori and described as “the Island Girl”, led an

invasion of Jutland (western Denmark) and captured

the German King Radigis of the Varni.

Aethelflaed, eldest

daughter of Alfred the Great of England

(c.

AD849—899), was

known as the Lady of Mercia and was at the forefront

of many battles against the invading Vikings.

Aethelflaed was also responsible for the

construction of a number of Anglo-Saxon

fortifications.

The Sutton Hoo

Sword

The sword is part of

a magnificent hoard of royal Anglo- Saxon treasures

found in a huge ship grave, in Suffolk, England, in

1939; its design is based on the earlier Roman

spatha, or cavalry sword. Its decoration includes a

hilt comprising a beautiful gold and cloisonné

garnet pommel and gold cross guard. The iron blade

is heavily corroded but the original pattern welding

is still identifiable and includes eight bundles of

thin iron rods hammered together to form the

pattern. This would have given the sword exceptional

strength, although it is more likely that it was

produced solely as a sumptuous grave gift.

|