Medieval Polearms

Massed formations of infantry

soldiers carrying polearms was a common sight on the

battlefields of Europe from the medieval period

right through to the early 1700's. The fighting part

of the polearm was placed on the end of a long shaft

and they were specially designed to disable and

inflict crushing injuries upon knights. Cheap to

produce in large numbers and versatile on the

battlefield, these weapons became the mainstay of

the European medieval foot-soldier when engaged in

close combat.

The Bardiche

A particularly brutal polearm

used extensively in medieval and Renaissance Europe,

the bardiche found particular favor in eastern

Europe and Russia. Blade design varied considerably

from country to country, but the main characteristic

was a substantial cleaver- type blade and attachment

to the pole by means of two widely spaced sockets.

Blade length was around 60cm (23.6in), although the

haft was unusually short at approximately l.5m

(4.9ft). This weapon appeared top-heavy and

impractical, but the bardiche was regarded more as a

heavy axe and wielded accordingly.

The Bill

With a tradition going back to

the Viking Age, the bill is commonly regarded as the

national weapon of the English both during and

beyond the medieval period, although it was used

elsewhere in Europe, particularly Italy. As with

many polearms, the bill developed from an

agricultural tool, the billhook, and displayed a

hooked chopping blade with several protruding

spikes, including a pronounced spike at the top of

the haft, resembling a spearhead. The bill also had

a strong hook for dismounting cavalry. Used

skillfully, it could snag onto any loose clothing or

armor and wrench the target from his horse and throw

him to the ground. English bills tended to be

shorter with the emphasis more on the chopping

action of the blade, while Italian bills had a very

long spiked end, resulting in its use as a thrusting

weapon.

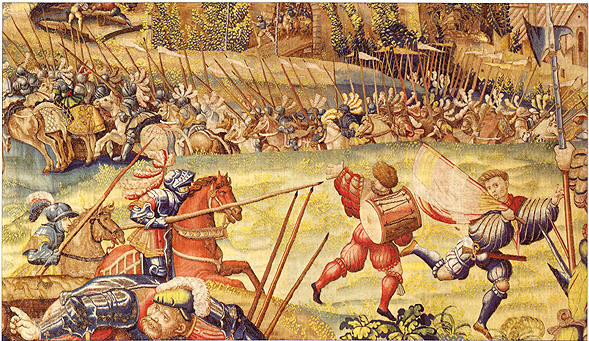

ABOVE:

The battle of Pavia, 1525, between the Holy Roman

Emperor Charles V and Francis I of France. Note the

pikes and halberds (right).

The Glaive

Similar in design to the

Japanese naginata, the glaive originated in France,

and its single-edged blade was attached to the haft

by means of a socket shaft. Blade length was

typically around 55cm (21.6in), with a wooden pole

l.8—2.lm (5.9—6.8ft) long. Medieval Swedish infantry

adapted the glaive by fixing a double-edged sword

blade to the haft. Glaives with small hooks are

known as “glaive-guisarmes”.

The Halberd

The halberd is a crude,

rectangular blade, shaped to a point at the top; the

earliest known use of the halberd comes from an

excavated example from the battlefield at Morgarten

(1315) in Switzerland. The word “halberd” originated

from the German haim (staff) and barte (axe). Over

time, the halberd’s spear point was improved to

allow it to be used to repel oncoming horsemen. The

haft of the halberd was also reinforced with thick

metal rims, making it more effective and durable

when blocking blows from an enemy sword or axe.

The Partizan

Smaller than normal polearms at 1.8—2m (5.9—6.6ft),

the partizan was constructed from a spearhead or

lancehead, with an added double axehead at the

bottom of the blade. It proved not to be as

effective as other polearms and it was gradually

withdrawn from frontline use. It remained as a

ceremonial weapon and many have elaborately

decorated blades. Partizans were carried right

through to the Napoleonic Wars (1804—15).

The Pike

A ubiquitous battlefield weapon during the medieval

period, the pike was simply a very long, thrusting

spear employed by infantry as both a static

defensive weapon against cavalry attacks and as an

attacking polearm, when used in massed ranks and

close formation. The combined length of both haft

and head rose over time to a staggering 3—4m

(9.8—13.lft), sometimes even 6m (19.6ft), and it was

this very length that was both its strength and also

its inherent weakness. The pikeman could stand at a

relatively safe distance from close combat, but the

weapon’s unwieldiness could also prove dangerous for

him. A pikeman was armed with sword, mace or dagger

in case his pike was lost in battle.

|