Ancient Greek weapons

The ancient Greeks

(c.

750—146Bc) regarded the sword

as strictly an auxiliary weapon, one that would

never supplant their battle-proven reliance on the

spear. The spear enabled the heavily armoured

hoplites, or infantrymen, to stand together and

protect each other within the close formation of

their phalanx wall of shields and spears. This

allowed them to repeatedly fight and win battles

against far superior opposition.

The

Hoplites The

Hoplites

Infantry foot-soldiers, the

ancient Greek hoplites (from the Greek word

hoplon, or armour) formed the military backbone

of the Greek city states. Hoplites were recruited

mainly from the wealthier and fitter middle classes,

and bore the financial responsibility to arm

themselves. Bronze armour, sword, spear and shield

all had to be provided from solely private means.

Hoplites were not full-time professional soldiers

whose only life was war. They had volunteered to

serve their state only in times of war (usually in

the summer), and, if they survived, would return

afterwards to their civilian roles. The hoplite was

a true manifestation of the classical Greek ideal of

shared civic responsibility.

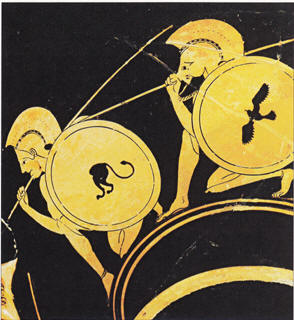

ABOVE:

Spartan hoplites, c.500Bc, wearing Corinthian

helmets. In addition to the shield and spear,

hoplites would have also carried a sword.

The Spear

A Greek

infantryman’s main battle weapon was the spear, or

doru. Measuring around 2.7m (8.8ft) in length, it

would have been held in one hand, while the shield (aspis)

was grasped in the other. The spearhead was

leaf-shaped, socketed and made of iron. At the butt

of the shaft was a sharp bronze spike, or sauroter

(“lizard killer”), which could be thrust into the

ground for added stability. In extremis, when the

spearhead was broken, the sharp spike could be

flipped around and used as a weapon of last resort.

The

Macedonians, under the leadership of Alexander the

Great (356—323BC), also developed their own spear or

pike, the sarissa. Little is known about it, but it

is thought to have been up to twice the length

(around 4—5m/13—16.4ft) of the doru and had to be

wielded underarm with two hands. This meant that the

usual protection of the shield-and-spear phalanx

could not be utilized, and so a small shield, or

pelte, was strapped to the left forearm. The

sarissa’s great length meant that it could keep the

opposing troops at a distance, enabling the

Macedonian cavalry to wheel around the flanks of an

enemy and strike with devastating effect. The

Macedonians, under the leadership of Alexander the

Great (356—323BC), also developed their own spear or

pike, the sarissa. Little is known about it, but it

is thought to have been up to twice the length

(around 4—5m/13—16.4ft) of the doru and had to be

wielded underarm with two hands. This meant that the

usual protection of the shield-and-spear phalanx

could not be utilized, and so a small shield, or

pelte, was strapped to the left forearm. The

sarissa’s great length meant that it could keep the

opposing troops at a distance, enabling the

Macedonian cavalry to wheel around the flanks of an

enemy and strike with devastating effect.

ABOVE:

Mosaic showing Alexander the Great, leader of the

Macedonians, hunting a lion with a doru (spear) in

the 3rd century

BC.

The Phalanx -

Ancient Armored Fist

Derived

from the Greek word

phalangos

(meaning “finger”), the hoplite phalanx was made up

of a tight formation of spearmen, armed with large,

concave shields that rested on the soldier’s left

shoulder and protected the man next to him, thus

forming an all- enveloping, locked curtain of

defence. The phalanx was typically about eight men

deep, with the front ranks projecting their spears

forwards. The key to the success of the phalanx was

the ability of the soldiers to keep together and not

break the formation. This was not always easy,

especially for the first few ranks, who were the

main combatants, as the rear ranks’ main purpose was

to continually push their phalanx forward and

maintain its shape. Derived

from the Greek word

phalangos

(meaning “finger”), the hoplite phalanx was made up

of a tight formation of spearmen, armed with large,

concave shields that rested on the soldier’s left

shoulder and protected the man next to him, thus

forming an all- enveloping, locked curtain of

defence. The phalanx was typically about eight men

deep, with the front ranks projecting their spears

forwards. The key to the success of the phalanx was

the ability of the soldiers to keep together and not

break the formation. This was not always easy,

especially for the first few ranks, who were the

main combatants, as the rear ranks’ main purpose was

to continually push their phalanx forward and

maintain its shape.

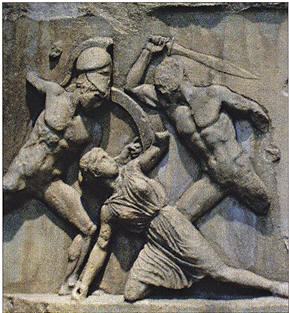

ABOVE:

A frieze from the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus,

c.35OBc,

depicting a mythical battle between the Greeks and

the Amazons.

There has been much debate as to how the spear was

used while in the phalanx: was it held aloft or

under the arm? Some authorities believe that it had

to be held aloft, as it would have been impractical

for a hoplite to hold his spear underarm, in case

the sharp butt spike injured the man behind him. The

use of the sword by the hoplites in the phalanx

would have been regarded as a highly dangerous

manoeuvre, because it necessitated breaking up the

shape and, consequently, the defensive cohesion of

the phalanx.

The Sword

There

is great irony in noting that the most successful

sword design of the Ancient World was developed by

the Greeks, who were ostensibly spearmen. The sword

was never regarded as a main battle weapon and

played a purely secondary role. Once the spears had

been thrown or lost in battle, swords were then

engaged to finish the conflict in a decisive manner. There

is great irony in noting that the most successful

sword design of the Ancient World was developed by

the Greeks, who were ostensibly spearmen. The sword

was never regarded as a main battle weapon and

played a purely secondary role. Once the spears had

been thrown or lost in battle, swords were then

engaged to finish the conflict in a decisive manner.

The main battle sword of the ancient Greek military

was the xiphos. Introduced around 800—400Bc,

it

comprised a straight,

double-edged, leaf-shaped blade of around 65cm

(25.6in), and was particularly effective at slashing

and stabbing. The Spartans carried a slightly

shorter sword of the same design as the xiphos. This

design probably influenced the later Roman gladius,

or short sword.

Mounted Greek cavalry used a curved sword, or

makhaira (meaning “to fight”). It had a large,

slightly curved falchion-type blade and was designed

to deliver a heavy slashing blow at speed.

The use of a curved blade for mounted horsemen would

remain a constant feature of cavalry swords for the

next 2,500 years.

ABOVE:

A stone depiction of Greek hoplites standing in

phalanx formation, from c.400BC.

|